The lye panic needs to stop

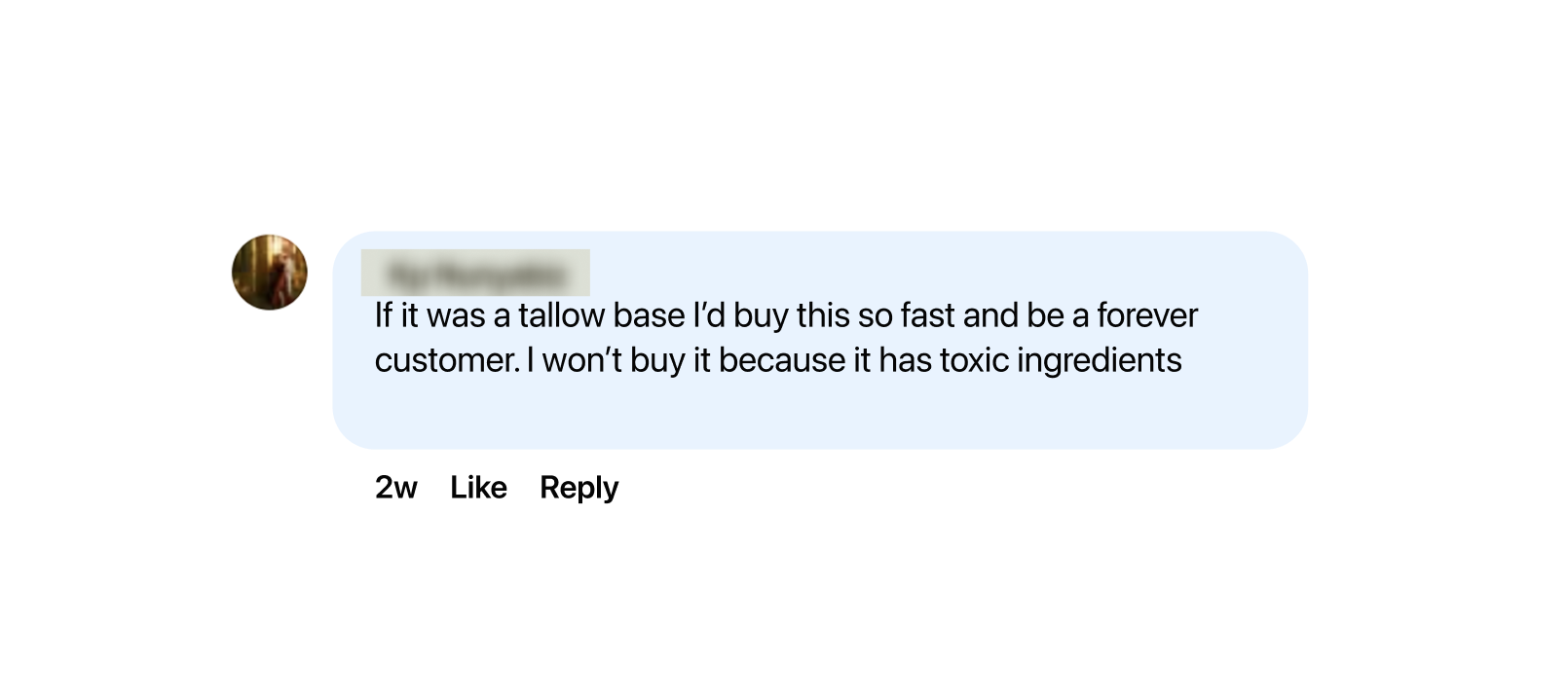

We’ve gotten something similar to this on an almost weekly basis: “Do you make soap without lye?” or “lye is toxic”

Short answer: Nobody does. It’s chemically impossible. I didn’t want to blow up at this comment on Facebook but even if it has tallow in it, it MUST use lye. So… stop lying on lye. (see what I did there?)

Long answer: Let me blow your mind about what’s actually happening in that bar.

First, the chemistry you need to know

Soap is literally just fat molecules that got rearranged by lye. That’s it. When lye (sodium hydroxide) meets oils, it breaks them apart and rebuilds them into soap molecules and glycerin[1]. This process is called saponification, and once it’s complete, there’s no lye left. Zero. None.

It’s like asking if there’s raw egg in your baked cake. The egg was essential to make the cake, but heat transformed it into something entirely different. Same with lye and soap.

Here’s what actually remains after saponification:

• Soap molecules (the cleaning part)

• Glycerin (3-5% in cold process soap)[2]

• Unsaponified oils (we leave 5-8% naturally for moisture)

If you’re wondering, what about that glycerin? Your skin makes it naturally. It’s what your body produces to keep skin hydrated[3]. Commercial soap companies extract it to sell separately to cosmetic companies, which is partly why grocery store soap dries you out. We leave ours in.

“But I saw soap labeled ‘lye-free’ at Whole Foods”

Marketing lies. They’re lying on lye (did it again). They either:

1. Bought pre-made soap base (someone else used the lye)

2. Used different words like “saponified oils of…” (that means lye was used)

3. Made detergent, not soap (synthetic surfactants, actually worse for skin)[4]

If it cleans and it’s actually soap, lye was involved. Period.

The poison myth started somewhere

Probably from someone’s grandmother or marketing scammers warning them about lye because raw lye IS dangerous. It’s caustic. It burns. You don’t want to touch it directly[5]. But that’s RAW lye, not soap.

Imagine being afraid of table salt because chlorine gas is poisonous (It took me a while to find a good reference and I’ll admit, I had to ask AI what a good comparison for this would be). When sodium (explodes in water) meets chlorine (literal poison gas), they become salt. Chemistry is weird like that.

What we actually do with lye

We measure precisely. Every oil needs a specific amount of lye to saponify completely[6]. Coconut oil needs more than olive oil. Shea butter needs less than palm. We calculate to the gram, then reduce by 5% so there’s extra oil left for your skin.

After mixing, the lye starts working immediately. Within 24-48 hours, saponification is 90% complete[7]. After our 3-week cure? No detectable lye remains. We could test it. We have. pH strips confirm it every batch.

Here’s what should actually concern you

Not lye, but:

• Synthetic detergents (SLS, SLES) that strip your skin[8]

• Artificial fragrances (up to 3,000 unlisted chemicals)[9]

• Preservatives needed because bars sat in warehouses for 18 months

• Extracted glycerin sold to make more money

We avoid all of this above. What we leave out keeps you safe. What we leave in is pleasure.

The bottom line

Being afraid of lye in soap is like being afraid of heat in cooking. It’s the process, not the product.

We use lye because that’s how soap is made. Has been for 5,000 years. Will be forever. Chemistry doesn’t care about marketing trends. (I may eat those words when everyone is an influencer.)

What’s in your shower was made with lye, whether the label admits it or not. The question is: was it made correctly, cured properly, and delivered fresh?

That’s what actually matters.

Black Altar We use lye. Then chemistry happens. Then it’s gone.

Sources: [1] Dunn, Kevin M. “Scientific Soapmaking: The Chemistry of the Cold Process.” Clavicula Press, 2010. [2] Cavitch, Susan Miller. “The Natural Soap Book.” Storey Publishing, 1995. [3] Fluhr, J.W., et al. “Glycerol and the skin: holistic approach to its origin and functions.” British Journal of Dermatology, 2008. [4] Wolf, R., et al. “Soaps, shampoos, and detergents.” Clinics in Dermatology, 2001. [5] NIOSH. “Sodium Hydroxide Safety Data Sheet.” CDC, 2023. [6] SAP values from multiple sources including Brambleberry Lye Calculator. [7] Kenna, L. “Cure Time and Saponification Rates in Cold Process Soap.” Journal of Cosmetic Science, 2019. [8] Bondi, C.A., et al. “Human and Environmental Toxicity of Sodium Lauryl Sulfate.” Environmental Health Perspectives, 2015. [9] Campaign for Safe Cosmetics. “Fragrance Disclosure.” 2024.